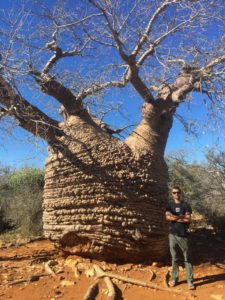

On May 22nd 2019 Elliot Smith and myself, Jake Bulman, hopped on a series of planes taking us from the Yucatan Peninsula where we live, across the world to Madagascar. In our bags we had packed all of our dive equipment, necessary clothes, and our underwater cartography equipment. We had a busy trip ahead of us including sub-fossil recovery, speleothem recovery and our main project, cartography.

Earlier that year we had taken a cartography class with Alessandro Reato, the cartographer behind the Sistema Minotauro map. Over three days he explained to us how to complete each part of the map with lots of tips, tricks, and even some impressive self-created methodologies. We left feeling prepared to go make our own map, however while we knew all of the steps involved, we underestimated the work involved in piecing them all together.

Now, this was our first Cartography project. This map was a critical part of the research papers the team of scientists (lead by Laurie Godfrey) and was going to publish with a large version of it to be posted at the entrance to the national park, and another at the cave entrance. Little did we know the true size of the task ahead of us. Internet at the resort was limited, basic resources used in modern cartography were unavailable, and we were on a very constrained time frame. Needless to say, it was a bit daunting. So we developed a plan based on the information we had about the actual site, the layout, logistics, and previously installed line. Looking back, we could have done things differently. However, we got it done and here is how we did it.

First Impressions Of The Site

Our first day at the site was intended to be a checkout dive. A chance for us to get a lay of the land, and to come up with a more precise plan. However we also decided to run a line around the entirety of the cavern to give us an idea of the size, depth, and space we were working with. Turns out, there was already a cavern line installed by the Madagascar Cave Diving Association (MCDA). We decided to run our own line anyway as the cavern line didn’t hug the walls as nicely as we would have liked, but that was not its intended purpose. This ended up being more difficult that I would have thought.

Alessandro Reato had told us that there was a lot of grey area when it comes to underwater cartography that is left up to the cartographer’s discretion. In this case, figuring out what areas should and should not be included highlighted this instantly. I had decisions to make. I would find myself in spaces that would clearly not be visited by cavern divers, yet was part of the daylight zone that I had set out to map. These areas had lots of bones (which I figured would be scientifically relevant), but would not be easily recoverable. From one side it would look irrelevant, then obviously relevant to the map once I approached from a different angle. While I had gone back and forth about it in my head, I made a decision on the boundary of the map, and am happy with it in the end. An Alex Reato quote, “Unless they have done a map themselves, nobody can say it’s wrong. It is your interpretation of the cave” came to mind.

The Mapping Process

We decided we needed five more days in the water to complete the map. This included installing and surveying over 1000ft of drawing lines with an average of 5.5m between tie offs, inputting all the data into Arianes line, tediously tracing (instead of printing – no printers!) all 200+ tie offs onto tracing paper, copying it all onto underwater drawing slates, drawing it all piece by piece the following days, creating a cross section, copying all the drawings on to tracing paper, measuring the distance between water surface and ground level, and gathering basic data like GPS coordinates. While I was the primary cartographer, the sheer amount of work was not possible by one person. Elliot’s support, ability to proficiently lay line, survey, trace, and copy was vital. Each day saw me in the water for at least four and a half hours, often beyond five. Elliot logged similar hours, although some of it was working on tasks above ground.

As we worked our way through the project we ran into pretty much every problem possible at one point or another. This was both frustrating and rewarding as we did manage to navigate our way through it eventually. Lots of late nights spent problem solving under the beam of a backup light hanging from the ceiling as the power was out at 11. Small survey errors, technology errors, overly ambitious timelines, software issues (always promptly solved by Sebastian Kister, even those that were user error), and other non-cartographical tasks that needed to be done all caused stress and delays. Beyond that, one very unexpected problem was a severe shortage of critical items such as tracing paper, pencils and drawing slates.

Closing The Project In Madagascar

After six more working days, I pieced together the drawings and laid it out on the table for the entire team to see. Everything fit together fairly well except for two small sections! Luckily we had taken photos of every step of the way and were able to fill in the gaps from those photos. We flew home treating the final tracing papers like our passports as without them the entire project would need to be redone.

Once home, I bought a printer, desk and a whiteboard and created a home office in the spare bedroom. It was now time to actually create the digital map. This was an entirely new challenge on its own. More info on this step, a few reflections on the project as a whole, lessons learned, and tips to my future self on the process as a whole will come in the next blog.

Until next time.

Article written by Jake Bulman