Close your eyes.

Continue to read this even though your eyes are closed.

Envision the space around you, what does it look like?

With your eyes still closed, reach out and touch the nearest object to you. What else is around you? Now open your eyes, how accurate were you? How were you able to do that?

Its unlikely you had consciously mapped the space around you directly prior to closing your eyes, and yet you were able to envision it nonetheless. Our minds are constantly absorbing, processing and storing information, and it all happens without any conscious effort on our part. That being said, we cannot process everything we see or hear, and we can’t make use of everything we do process. However, oftentimes we do not allow our brain do this work. For example, would you be equally accurate if you were simultaneously having a stressful discussion with your boss? What if you were in a totally new environment? Or if instead of the organized, tidy space I’m sure you occupy, you had a space cluttered with odds and ends? What if you were trying to balance on one foot? How would your performance compare? What has changed?

When we introduce this concept in class, we often use the analogy of a water bottle. This water bottle represents our available mental capacity to absorb, process, and utilize information to accomplish a task, learn new skills or otherwise devote our attention. When you started reading this and closed your eyes, you were likely sitting or laying down. This doesn’t require any attention, so doesn’t fill your “mental water bottle” at all. Then you found that you could reach out and touch the nearest object to you without looking, maybe you even tried other objects and found you could do the same. That unused space was not actually unused, it was subconsciously soaking up information from your senses and processing it in case you needed it. This unused space allows for awareness.

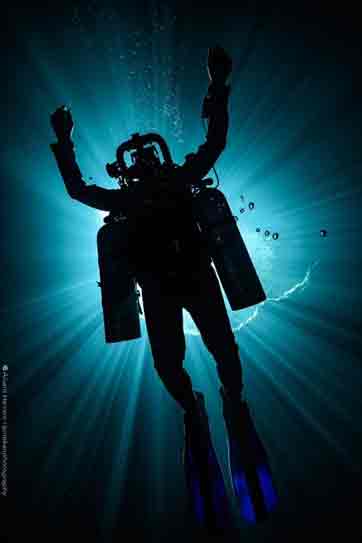

While awareness is the word we use, it is only a part of what we actually want to achieve. Being aware of something is one thing, being able to take that information and critically apply it to how you perceive a situation is the part that makes the difference. This step brings us to another term we hear around the industry, which is being a “thinking diver”. Awareness and “being a thinking diver” offer endless benefits, but this article is not about that. What I want to focus on is what we can do to improve these two things.

As we have seen, our brain does a lot of this on its own. It may not solve complex puzzles without conscious effort, but let’s be honest, diving doesn’t tend to include complex puzzles. It will also only be able to utilize information based on our knowledge and experiences. It can’t teach us cause and effect underwater, but it will apply past experiences to estimate an outcome. In order for our brains to do this, we need to reduce the amount of space we are using in our mental water bottle. This is done via two methods. First, we can develop strong, consistent fundamental skills. Secondly, we can make our lives underwater as easy as safely possible.

First, our fundamental skills. As many of you know, being still in the water while not moving is one of the hardest things to learn. The more we swim, the more we can compensate with our fin kicks for any instability or buoyancy problems. It is not a conscious thought for most people that “I’m sinking just slightly, let me adjust my kick slightly to compensate”, but those subconscious calculations and thought processes do use up space.

This inability to stay still also creates a constantly moving, dynamic scenario instead of a static, controlled one, which comes with its own host of not-the-focus-of-this-article problems. To use the same analogy, we had earlier when we closed our eyes, this would be trying to jump on one foot while doing the same test.

Once a diver is able to do nothing and just sit still comfortably, the available space for awareness/thinking increases dramatically. This takes some training and practice, but is the first step to emptying our “mental water bottle”. Fortunately for us all, it is a skill with no upper limit. You can always improve. If you reach a point where you believe you cannot improve, you will stop improving, proving yourself correct while at the same time being deeply incorrect.

On the other hand, you can be the most talented diver in the world but if you are diving in a way that is inherently difficult, managing this added difficulty will cost you space as well. For instance, one of the most common misconceptions I see in class is that more gas/tanks is always safer. Healthy reserves are important and required, but adding more and more tanks can create a configuration that is going to cause more problems than it solves. I’m going to refer to this as “diveability”.

This leads us to our second method of freeing up mental space… making our diving easier. The first day of class almost always involves discussions about equipment, at any level of training. Teaching CCR Cave especially has meant quite lengthy conversations about different approaches to configurations, as many students are long time professionals, cave explorers, cave instructors and instructor trainers. I am here to teach them how best to use rebreathers in the cave and share my point of view on various subjects, not force my precise way of diving on everything they do. Beyond that I need to ensure they are making informed, educated decisions about their equipment with an understanding of the pros/cons that come with it.

The most common point of contention is the amount of stuff people bring with them. For example, you can make a case for the value in bringing spare mouthpieces/o rings/zip ties/multi-tools/markers. A case could also be made for extra D-rings, in-line shut offs/flow stops, extra bail out tanks, extra dump valves, three safety spools, an entire toolbox, a tag along underwater regulator service technician and a spare set of fins clipped to these extra D-rings.

Each and every one of you felt some of these were reasonable, and some of these were not. You may feel that some are reasonable only in certain situations or environments.

My goal is not to tell you what to bring, but to consider what you lose in diveability by doing so. Every student always justifies every item they bring, but a line does need to get drawn somewhere. My line likely gets drawn in a different place than yours, which is different from the next person.

I can’t tell you where to draw your line, but what I can say for sure is that time and time again, these items cause problems in class. Snagging on a line, making it difficult to find what they are looking for, making them too heavy or preventing them from more complex diving because there is no space left for deco bottles or to tow a scooter.

Every item we bring fills up our water bottle, even if only a drop. Every imbalance we have, every buoyancy struggle, every extra liter of gas in our BCD, all reduce available space for awareness and critical thinking. What we need to ask ourselves is, is the safety provided by this item worth the cost in diveability? Could we improve our own diving skills and allow our brains to better do their jobs? Nobody can answer all of these for us, but divers mental water bottles overflow all the time and what seems like basic things become difficult, problems happening in front of our eyes go unnoticed and incidents happen that are totally preventable. I have been there, you have been there, we all have at one point.

In this way, awareness is not a skill that is learned, but a state that is earned. Earned through development of foundational skills, choices regarding equipment and procedures, an open mind, and a healthy amount of self reflection on what we can do better.